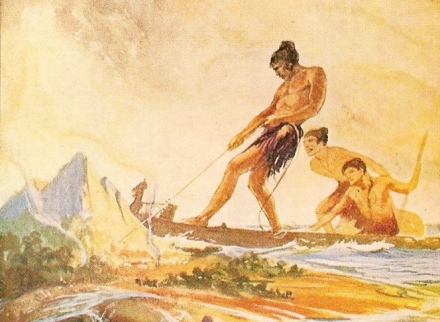

In Polynesian mythology, Maui is a powerful, intelligent demigod. He’s featured in some of the most important Maori myths, and his resume includes snaring the sun out of the sky and taming fire.

Perhaps the most well known story is of Maui hauling the north island of New Zealand out of the ocean, using blood from his nose for bait.

According to the story, Maui is fishing with his brothers, seated on a canoe symbolic of New Zealand’s south island. Far out to sea, the brother drop an anchor into the water, and using a jawbone as bait, Maui catches a monstrosity of a fish. He leaves the fish with his brothers to find a priest to bless the catch, and in his absence they gut the fish, gouging the north island’s mountains and valleys into its flesh. To this day, the north island is considered to be Maui’s fish (Te Ika), the south island is known as Maui’s canoe (Te Waka).

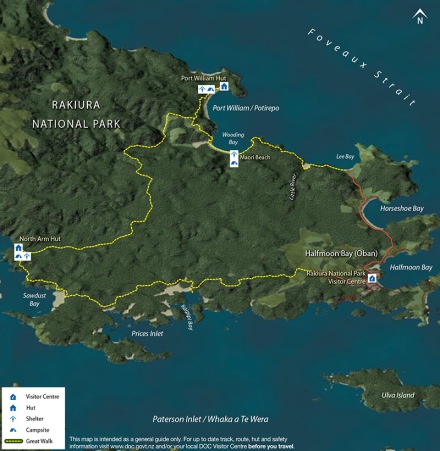

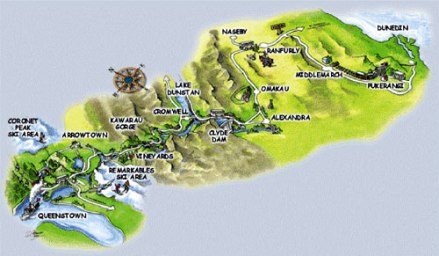

Since arriving in New Zealand, I’ve traveled across Maui’s canoe and his fish, flying into Auckland in February and scooting down the north island, then living in Dunedin and backpacking around the south island nearly every weekend this semester. But there is one more island in the triad along with Maui’s canoe and his fish, and that is Maui’s anchor stone (Te Punga), which allowed his canoe to hold fast while he hauled up the giant fish. That anchor is Stewart Island, or Rakiura (the Maori name), one of the southernmost landmass on earth with a permanent residential population.

Only 381 people live on Stewart Island year round, most of them in the island’s only town, Oban. It’s a remote, forested island dominated by a swampy river valley, with a vibrant native bird population due to the relative absence of rodent predators. If you’re lucky, you can see the Aurora Australis (Southern lights) from the island. But despite its southerly location, the island has a remarkably temperate climate, good enough for shorts in the fall.

To get to the island from mainland New Zealand, you can either fly or take the hour-long, 130-dollar ferry that cuts across 30 kilometers of the Foveaux Strait. For Anzac Day weekend (a holiday weekend that commemorates all New Zealanders killed in war), me, and five other friends crossed that strait at the bottom of the world to explore the remote jungley terrain of Maui’s anchorstone.

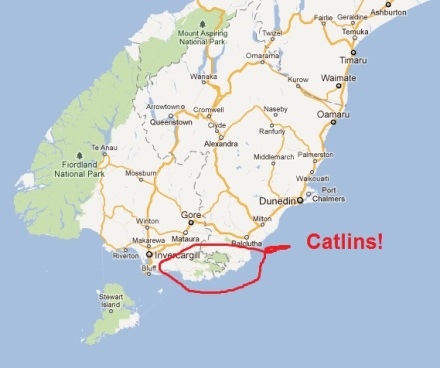

We took off on a Friday and cut south toward the southerly tip of the south island. We took our time passing through the rolling verdant hills and rugged oceanside cliffs of the Catlins, a region on the far southeastern coast of the south island that feels reminiscent of Scotland or Ireland. It’s sprinkled with patches of sunny temperate rainforest and gorgeous waterfalls. Although the Catlins area hosts a population of only about 1200, the exposed location, wild weather and heavy ocean swells make the area a secret gem for big wave surfers.

On Friday, our Stewart Island crew consisted of me, Riz, Tim, Micah, Sam, Drew, Bri and her brother, but when Bri and bro saw the incredible surf hitting the Catlin coast and the stellar weather forecast, they opted to stay on the beach for the weekend.

The Catlins: Hike to Purakaunui Falls through the temperate rainforest:

Purakaunui Falls:

The surf…

We camped at a Holiday Park in Bluff, the southerliest town on New Zealand’s south island and the take off point for Stewart Island. It’s a blustery sea port with a population of less than 2000; we didn’t spend much time there but did check out the local bar for a quick brew. The small-town feeling reminded me of Collingwood, but Bluff seems more rugged and exposed in contrast to Collingwood’s homey and protected location in peaceful Golden Bay. Something about that pub reminded me of the pub in the movie “The Perfect Storm.”

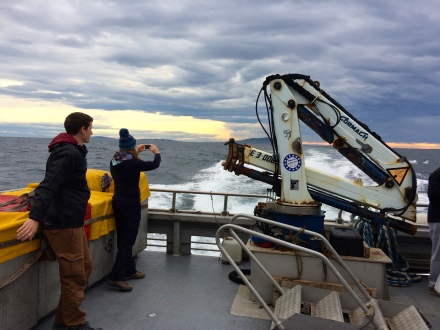

We woke the next morning to gray skies and a 9am boat, and were off on our way south, the farthest south most of us will probably go in our lives, unless we make it to Antarctica. The mood was stormy and subtly dramatic, perfect for the crossing, but the clouds steadily burned off in the late morning sun. Throughout the ferry ride an eerie yet gorgeous band of brilliant yellow rimmed the horizon just above the sea, like a sunrise that lasted four hours. We passed craggy rock island and forested islands populated only by birds, sprinkled throughout the choppy slate gray waves.

Unlimited free coffee on the ferry made up for the exorbitant price; by the time we docked we were ready with backpacking packs packed and nerves stoked on caffeine.

Morning ferry ride to Stewart Island:

The ferry docked at Halfmoon Bay in the island’s only town, Oban. To start the track we had to get to Lee Bay, so we had to walk about 40 minutes along a road winding along the island’s coast. I couldn’t complain; it was gorgeous and remote and we saw about two people and one car throughout the walk. The environment reminded me a bit of Vashon, but even more rugged and with an exotic, jungley feel. The road crested hills from which we could peer down at shallow bays and beaches slowly lightening and turning blue with the strengthening sun. Our goal for the night was North Arm hut, where we’d meet up with a group of Arcadia girls also doing the hike.

Along the road:

The first stretch of the walk itself follows the shoreline along pristine, isolated beaches and bays. We cut in and out of mossy forests and walked across segments of fine, white sand beaches covered in an array of rainbow conch shells and mussels, as the sun slowly burned off clouds and the sky brightened to a robin’s egg blue. There was virtually no one to be seen; the landscape felt like a scene from Castaway or Survivor. Flocks of native birds congregated on still beaches, and albatross — the largest birds in the world– flapped their heavy wings in the distance. From far away you would think they were seagulls, but up close they are ludicrously enormous. I don’t know if it came from simply knowing we were on a remote island or if the feeling was real, but the Rakiura track felt wild, mystical and almost fanstastical, as if any imagined creature could trot out of the woods or rise out of the water.

Eventually the trail left the beaches and cut through Stewart Island’s forests. They are dense, green and muddy, but welcoming let in a dappling of light. We bisected the forested island from Port William to North Arm Hut, a stretch that seemed to last forever. In the afternoon we passed an iconic “half way tree”– apparently, rangers from the Department of Conservation will mark trees as “halfway trees” regardless of if they actually mark the halfway point or not; apparently a lot of them are practical jokes on tired hikers, who will be pleasantly surprised and think they’re either almost to their destination, or will be shocked by how long they still have to walk. This halfway tree was marked by a massive buoy hanging in the branches. I can’t imagine how a ranger lugged it all the way there!

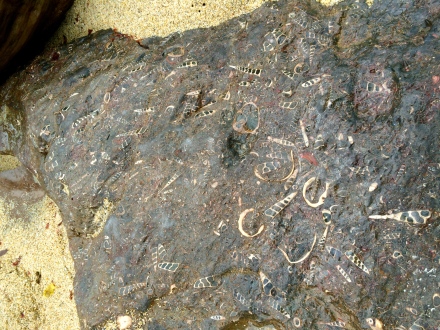

The sky darkened again as evening approached and we walked quickly to get to North Arm in time to set our tents up in the last patch of light, right before the rain hit. The North Arm hut sits on Paterson inlet, formerly a river system that was submerged when sea level rose after the last ice age. Maori once collected shells from the inlet to use to line trails through the bush and ate shellfish from its waters; it’s now a marine reserve.

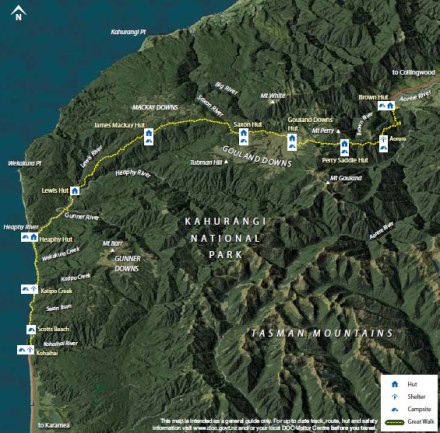

We scurried over to the hut to take advantage of shelter and say hi to the group of Arcadia girls staying there, and stayed late into the night playing cards, unwilling to hike back to our tents in the pouring rain. In the middle of the night, we were awoken by the shrill cry of… a kiwi! After Riz and I’s misidentification on the Heaphy track, we had done our research and this time I’m sure it was the iconic New Zealand bird. Although they’re endangered, 20,000 kiwi still live on Stewart Island. Being so remote, it’s their last refuge. Unfortunately I was too cozy in the tent to get out in the rain and kiwi hunt, but I was content with knowing they were hopping around in the area.

When we woke up it was still raining. Luckily it was our short day, the hike back to town where we all planned on grabbing fish and chips and a beer. Although the rain drizzled down and the path was unreasonably muddy, I may have enjoyed that day more. The woods were calm, hushed and mystical, and the rain only added to the magical feeling of being removed from the world and placed in a fantasy land. We walked through thick beds of dripping ferns of jurassic size and passed by still inlets cloaked in misty veils of gray, where birds lined the sand and took off in graceful lines through the rain.

North Arm hut:

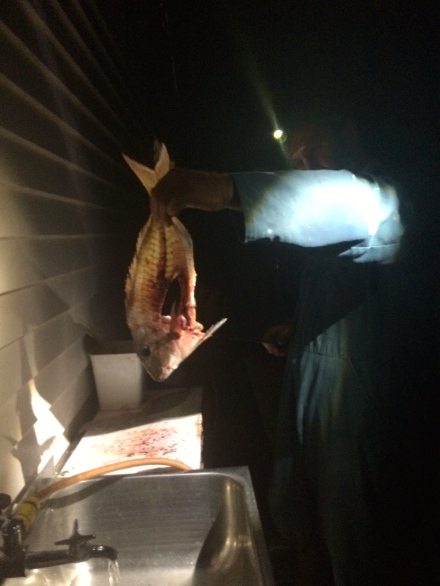

Back in Oban, we were starving and wet; we cozied up in a warm, homey pub and grabbed the fish and chips and beer we’d all been craving. We sat on couches looking out the pub window at the harbor and watched as the sun emerged again, just in time for a spectacular ferry ride back to Bluff. As we waited on the doc, a double rainbow appeared across the harbor, some of the strongest colors I’ve seen in a rainbow– you could see purple! The sky was dazzling, and filled with albatross. They looked truly joyous, soaring behind our boat and diving to clip their wing tips on the waves. I didn’t even get a free coffee– this view made the pricey ferry worth it.

After Stewart Island, the Middle Earth journey is one more step towards completion. Although I still have a few more weeks left to adventure and a lot more to see, visiting all three islands and all three characters in Maui’s myth is crucial. Stewart Island may be the farthest south I’ll ever go, but I hope not… with a little taste of the southerly extremes, I think Antarctica is on the horizon…..

The ride back:

The drive:

The drive: